Clinical Study

Bird Flu Outbreak of 2024-2025: Current Status on Prevention and Control

Dr. Pallavi Upadhyay • Apr. 16, 2025

Avian Influenza Viruses: Origin and Background

Avian Influenza Virus A (H5N1) belongs to the Influenza A genus (family Orthomyxoviridae)1. Avian flu (AIV) spreads zoonotically from infected poultry and other farm animals to humans. AIVs (also referred to as H5N1, bird flu or avian flu viruses) are RNA viruses with a characteristic segmented genome, allowing for the frequent genetic reassortment and antigenic shifts, which in turn facilitates the virus to rapidly evolve and adapt to new host environments1,2. These viral properties make AIVs a significant and unpredictable threat to mankind2. Experts believe that just like its cousin (common flu), avian flu has the potential to become a pandemic2.

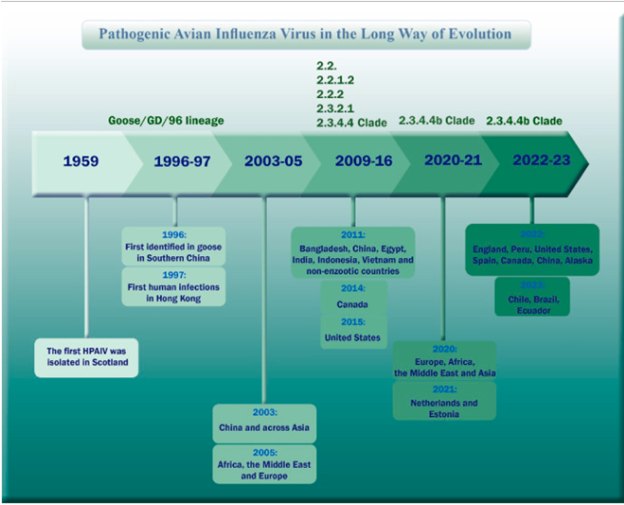

Figure 1 depicts the mechanism of zoonotic transmission of H5N1viruses from birds to mammals (Peiris et al., 2007)2.

Figure 1. Image sourced from Peiris JSM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. 2007. Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1): A Threat to Human Health. Clin Microbiol Rev 20.

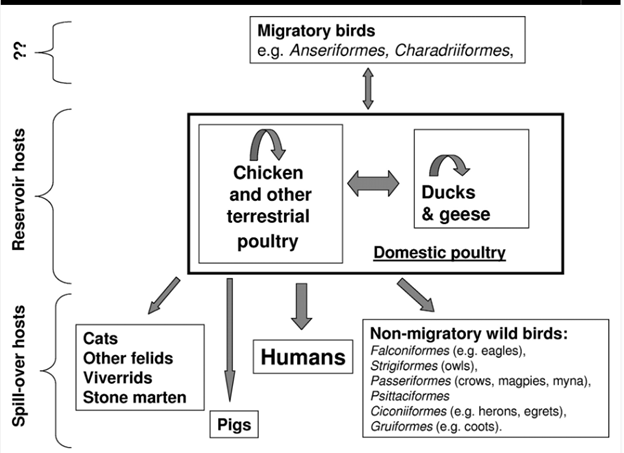

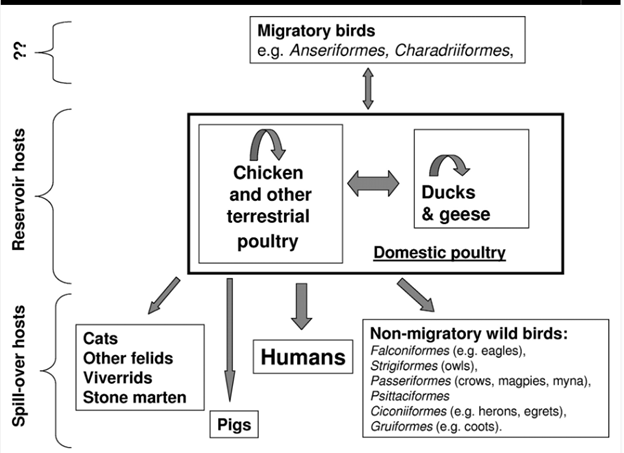

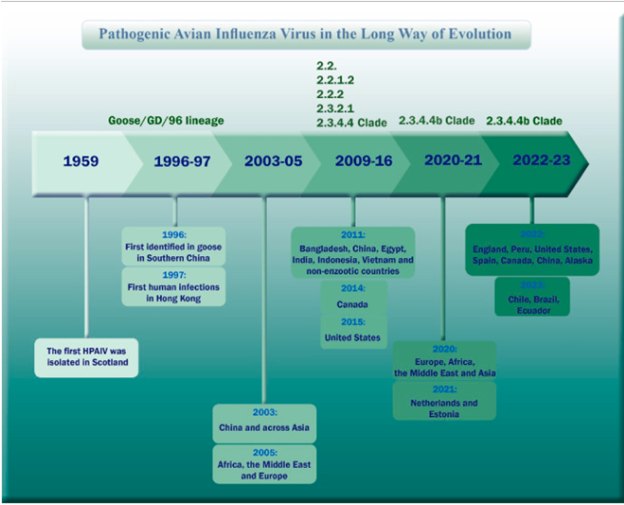

AIVs are categorized as Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) subtypes based on their pathogenicity and severity of clinical presentations in chickens. LPAI viruses can convert to HPAI viruses and thus both types and their positivity (and outbreaks) should be monitored during surveillance3. Among the various HPAI strains, the H5N1 virus is considered highly pathogenic. The first avian flu cases were noted in 1959 in poultry in Scotland. And the first outbreak of bird flu in humans was reported in Hong Kong in 1997. Since then, several HPAI/H5N1 outbreaks have been reported in multiple countries. Refer to Figure 3 for a detailed timeline of the H5N1 outbreaks from 1959s to recent years across various countries4.

Figure 2. The timeline of the H5N1 outbreaks from 1959 to recent years across various countries.

Image sourced from: Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V and S, Bashash D, Hashemi SM, Nakhaie M, Zandi K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2023 Sep 1;55:102638.

Clinical Presentation in Humans

The time from first exposure with avian flu viruses to the start of respiratory distress is approximately 72 hours (but may range from 48 to 96 hours). In addition, ocular symptoms/conjunctivitis (eye redness and swelling) can show in 24 to 48 hours of the first exposure5. While most cases of bird flu in humans have been mild, with most individuals impacted being in the proximity of livestock, severe case can lead to hospitalization and death.

Some mild symptoms of bird flu are conjunctivitis, fever, and other symptoms similar to H1N1 (common flu). Moderate symptoms include dyspnea, high fever, seizures, etc. Severe and Complicated cases may show symptoms of respiratory failure, pneumonia, sepsis, multi-organ failure and meningoencephalitis (sever inflammation of brain)5,6.

Disease Burden and Current Situation

In the past sixty-five years, H5N1 has posed significant challenges to the public health and economy worldwide. In addition to economic burden, H5N1 infection spread can overwhelm the healthcare sector. According to the CDC and WHO, more than 1000 cases of human infections with bird flu have been reported since 2003 with approximately 50% cases resulting in mortality7,8,9. The recent outbreak of 2024-2025 in the United States with 70 confirmed cases of human H5N1 infection and one case of death has alerted the public and health experts8. In addition, emerging or re-emerging pathogenic AIV strains, such as H7N9, continue to add to the global influenza burden. Since the first reported case of H7N9 in humans, It has led to more than 1500 human infections10. The first outbreak subtype H7N9 in the United States occurred 2017. This outbreak was reported in poultry and livestock. With no reported outbreaks since 2017 within the United States, the poultry industry is alerted due to a recent H7N9 outbreak in March 2025 in Mississippi11. This H7N9 re-emergence has spurred a worry among the healthcare sectors. Due to its high pathogenicity with a high mortality rate (approximately 40%), this strain has the potential to cause epidemics and even a pandemic.

Prevention, Treatment and Diagnostic Strategies

The H5N1 viral infection is widespread amongst bird populations within the United States, making it crucial that the public understands best practices on how to prevent spread of this potentially deadly disease. Noteworthy, despite the successful replication of the virus in humans, fortunately, sustained human-to-human transmission has not been noted yet.

A. Prevention measures

As always, prevention is better than treatment – protecting yourself, if you work with poultry and herds, from the virus would entail the following steps:

- Reporting of ill and dead livestock.

- Wearing protective gear while in contact with livestock, in general.

- Avoid consumption of raw farm-derived dairy.

- Vaccination/Immunization is suggested for those at risk.

Elaborating on vaccinations: According to the CDC, vaccines against seasonal flu are a preventative measure for individuals that are exposed to poultry and can be exposed to potential infections. From 2007 to 2020, the US has licensed three H5N1-focused vaccines. The target populations for these vaccines are the individuals have considerable risk for exposure (mainly livestock and poultry workers). In addition, for pandemic preparedness against H5 influenza viruses, the EMA (European Medicines Agency) has also authorized six additional vaccines.

The WHO curates a list of candidate vaccines for H5N1 and other zoonotic influenza viruses, updated biannually per the flu seasons12. In the US, the CDC has developed an H5 vaccine candidates which can be used for at-risk populations (farm workers, livestock handling professionals, etc.)13. In a nutshell, at present, globally, several private (Moderna, Astra Zeneca, Sinergium Biotech, etc.) and public health organizations (The CDC, WHO, EMA) are developing H5N1 vaccines13-16.

B. Treatment

Supportive care, with over-the-counter fever reducers and painkillers, enhanced fluid intake, rest and oxygen therapy, play a significant role towards relief from bird flu infections. Antivirals are the first medical interventions against infectious viral diseases. It is recommended that the treatment regime should begin within 48 hours of exposure or onset of symptoms. Due to these reasons, practitioners often prescribe them empirically until the lab results are back. Some of the common antivirals that are prescribed against bird flu are: oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza) or peramivir (Rapivab)13, 17.

C. Avian Flu Diagnostic Tools

- Molecular or Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs):

While many molecular tests [e.g., Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA); Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP); Nuclear Acid Sequence-Based Amplification (NASBA); Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)] can detect H5N1 in clinical samples, the preference of real time RT-PCR (with multiplexing capabilities) for H5N1 identification is due to the test’s high specificity and sensitivity teamed with quicker turnaround time for results. Given these advantages, the CDC endorses RT-PCR as the frontline diagnostic tool for the detection of H5N117,18.

- Serological tests:

Several tests, like Hemagglutination Inhibition and ELISA, which detect the presence of antibodies against H5N1 in poultry samples are available, but none have been approved for diagnostic testing in humans18,19. These tests generally have lower sensitivity and may display cross reactivity with antibodies against other seasonal Influenza strains. A microneutralization assay can be highly specific for the detection of H5N1, but it is a resource and time intensive technique that cannot be used in routine diagnostics. However, these tests are important tools in pandemic preparedness and vaccine evaluations.

Conclusion and Path Forward

The recent H5N1 Outbreaks viruses have taken a great toll on the poultry industry within the United States, which in turn has directly or indirectly impacted both healthcare and the economy at large. Pandemic Preparedness strategies that involve pharmaceutical as well as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), as follows:

- Surveillance: Monitoring the transmission rate and pattern is paramount for early detection, information to public health sectors and containment strategies. Surveillance enables identification and characterization of emerging strains and prompt risk assessment. Global (collaborative network of WHO11 and its Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System) as well as national Surveillance systems (e.g., Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – APHIS), monitor emergence of AIV strains, allowing for timely intervention and response measures.

- Diagnostics: As viruses mutate and evolve, leading to novel and more pathogenic strains, diagnostic preparedness for AIV should encompass a comprehensive diagnostic approach to eventually include emerging and re-emerging strains (e.g., H7N9, H5N4, etc.) to ensure accurate and timely detections that will allow health officials and practitioners to make informed treatment interventions, ultimately protecting human and animal health.

- Effective Vaccines and Treatment: As discussed above, due to the constant evolution of viruses and potential for mutations to adapt to new hosts, research and development into more universal vaccines as well as novel therapeutics will be crucial to be effective against emerging strains with a pandemic potential.

Public-Private partnerships will be crucial to drive and accelerate the afore-mentioned strategies into action to combat the spread of disease and prepare for any potential pandemic. Enhancing global collaboration and promoting public health education will strengthen the preparedness and response strategies for future pandemics.

References

- de Jong MD, Hien TT. Avian influenza A (H5N1). Journal Clin Virol. 2006. 1;35(1):2-13.

- Peiris JM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 2007. 20(2):243-67.

- WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 evolution working group. Continued evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1): updated nomenclature. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2012. 6(1):1-5.

- Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V et al. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023. 1;55:102638.

- Hui DS. Review of clinical symptoms and spectrum in humans with influenza A/H5N1 infection. Respirology. 2008. 13:S10-3.

- CDC. What are the symptoms of H5N1 bird flu. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/video-series/symptoms-h5n1.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. First H5 Bird Flu Death Reported in United States. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/m0106-h5-birdflu-death.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- WHO. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024, 12 December 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who–2003-2024–20-december-2024. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Asian Lineage Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm. Accessed 4/14/2025.

- H7N9 avian flu strikes Mississippi broiler farm. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/h7n9-avian-flu-strikes-mississippi-broiler-farm. Accessed 4/12/2025.

- WHO. Global Influenza Programme. https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Avian Influenza A Viruses in People. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/index.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- American Society of Microbiology. Avian Influenza (H5N1) Vaccines: What’s the Status? https://asm.org/articles/2025/march/avian-influenza-h5n1-vaccines-what-status. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 AstraZeneca (previously Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 Medimmune). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/pandemic-influenza-vaccine-h5n1-astrazeneca. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Vaccines for pandemic influenza. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/public-health-threats/pandemic-influenza/vaccines-pandemic-influenza. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/hpai-interim-recommendations.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection and Testing for Patients with Suspected Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease or with the Potential to Cause Severe Disease in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/severe-potential/index.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

- CDC. CDC Report on Missouri H5N1 Serology Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/missouri-h5n1-serology-testing.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

References

- de Jong MD, Hien TT. Avian influenza A (H5N1). Journal Clin Virol. 2006. 1;35(1):2-13.

- Peiris JM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 2007. 20(2):243-67.

- WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 evolution working group. Continued evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1): updated nomenclature. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2012. 6(1):1-5.

- Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V et al. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023. 1;55:102638.

- Hui DS. Review of clinical symptoms and spectrum in humans with influenza A/H5N1 infection. Respirology. 2008. 13:S10-3.

- CDC. What are the symptoms of H5N1 bird flu. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/video-series/symptoms-h5n1.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. First H5 Bird Flu Death Reported in United States. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/m0106-h5-birdflu-death.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- WHO. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024, 12 December 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who–2003-2024–20-december-2024. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Asian Lineage Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm. Accessed 4/14/2025.

- H7N9 avian flu strikes Mississippi broiler farm. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/h7n9-avian-flu-strikes-mississippi-broiler-farm. Accessed 4/12/2025.

- WHO. Global Influenza Programme. https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Avian Influenza A Viruses in People. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/index.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- American Society of Microbiology. Avian Influenza (H5N1) Vaccines: What’s the Status? https://asm.org/articles/2025/march/avian-influenza-h5n1-vaccines-what-status. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 AstraZeneca (previously Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 Medimmune). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/pandemic-influenza-vaccine-h5n1-astrazeneca. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Vaccines for pandemic influenza. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/public-health-threats/pandemic-influenza/vaccines-pandemic-influenza. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/hpai-interim-recommendations.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection and Testing for Patients with Suspected Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease or with the Potential to Cause Severe Disease in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/severe-potential/index.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

- CDC. CDC Report on Missouri H5N1 Serology Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/missouri-h5n1-serology-testing.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

Related Articles and White papers

Dr. Pallavi Upadhyay • Apr. 16, 2025

Avian Influenza Viruses: Origin and Background

Avian Influenza Virus A (H5N1) belongs to the Influenza A genus (family Orthomyxoviridae)1. Avian flu (AIV) spreads zoonotically from infected poultry and other farm animals to humans. AIVs (also referred to as H5N1, bird flu or avian flu viruses) are RNA viruses with a characteristic segmented genome, allowing for the frequent genetic reassortment and antigenic shifts, which in turn facilitates the virus to rapidly evolve and adapt to new host environments1,2. These viral properties make AIVs a significant and unpredictable threat to mankind2. Experts believe that just like its cousin (common flu), avian flu has the potential to become a pandemic2.

Figure 1 depicts the mechanism of zoonotic transmission of H5N1viruses from birds to mammals (Peiris et al., 2007)2.

Figure 1. Image sourced from Peiris JSM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. 2007. Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1): A Threat to Human Health. Clin Microbiol Rev 20.

AIVs are categorized as Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) subtypes based on their pathogenicity and severity of clinical presentations in chickens. LPAI viruses can convert to HPAI viruses and thus both types and their positivity (and outbreaks) should be monitored during surveillance3. Among the various HPAI strains, the H5N1 virus is considered highly pathogenic. The first avian flu cases were noted in 1959 in poultry in Scotland. And the first outbreak of bird flu in humans was reported in Hong Kong in 1997. Since then, several HPAI/H5N1 outbreaks have been reported in multiple countries. Refer to Figure 3 for a detailed timeline of the H5N1 outbreaks from 1959s to recent years across various countries4.

Figure 2. The timeline of the H5N1 outbreaks from 1959 to recent years across various countries.

Image sourced from: Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V and S, Bashash D, Hashemi SM, Nakhaie M, Zandi K. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2023 Sep 1;55:102638.

Clinical Presentation in Humans

The time from first exposure with avian flu viruses to the start of respiratory distress is approximately 72 hours (but may range from 48 to 96 hours). In addition, ocular symptoms/conjunctivitis (eye redness and swelling) can show in 24 to 48 hours of the first exposure5. While most cases of bird flu in humans have been mild, with most individuals impacted being in the proximity of livestock, severe case can lead to hospitalization and death.

Some mild symptoms of bird flu are conjunctivitis, fever, and other symptoms similar to H1N1 (common flu). Moderate symptoms include dyspnea, high fever, seizures, etc. Severe and Complicated cases may show symptoms of respiratory failure, pneumonia, sepsis, multi-organ failure and meningoencephalitis (sever inflammation of brain)5,6.

Disease Burden and Current Situation

In the past sixty-five years, H5N1 has posed significant challenges to the public health and economy worldwide. In addition to economic burden, H5N1 infection spread can overwhelm the healthcare sector. According to the CDC and WHO, more than 1000 cases of human infections with bird flu have been reported since 2003 with approximately 50% cases resulting in mortality7,8,9. The recent outbreak of 2024-2025 in the United States with 70 confirmed cases of human H5N1 infection and one case of death has alerted the public and health experts8. In addition, emerging or re-emerging pathogenic AIV strains, such as H7N9, continue to add to the global influenza burden. Since the first reported case of H7N9 in humans, It has led to more than 1500 human infections10. The first outbreak subtype H7N9 in the United States occurred 2017. This outbreak was reported in poultry and livestock. With no reported outbreaks since 2017 within the United States, the poultry industry is alerted due to a recent H7N9 outbreak in March 2025 in Mississippi11. This H7N9 re-emergence has spurred a worry among the healthcare sectors. Due to its high pathogenicity with a high mortality rate (approximately 40%), this strain has the potential to cause epidemics and even a pandemic.

Prevention, Treatment and Diagnostic Strategies

The H5N1 viral infection is widespread amongst bird populations within the United States, making it crucial that the public understands best practices on how to prevent spread of this potentially deadly disease. Noteworthy, despite the successful replication of the virus in humans, fortunately, sustained human-to-human transmission has not been noted yet.

A. Prevention measures

As always, prevention is better than treatment – protecting yourself, if you work with poultry and herds, from the virus would entail the following steps:

- Reporting of ill and dead livestock.

- Wearing protective gear while in contact with livestock, in general.

- Avoid consumption of raw farm-derived dairy.

- Vaccination/Immunization is suggested for those at risk.

Elaborating on vaccinations: According to the CDC, vaccines against seasonal flu are a preventative measure for individuals that are exposed to poultry and can be exposed to potential infections. From 2007 to 2020, the US has licensed three H5N1-focused vaccines. The target populations for these vaccines are the individuals have considerable risk for exposure (mainly livestock and poultry workers). In addition, for pandemic preparedness against H5 influenza viruses, the EMA (European Medicines Agency) has also authorized six additional vaccines.

The WHO curates a list of candidate vaccines for H5N1 and other zoonotic influenza viruses, updated biannually per the flu seasons12. In the US, the CDC has developed an H5 vaccine candidates which can be used for at-risk populations (farm workers, livestock handling professionals, etc.)13. In a nutshell, at present, globally, several private (Moderna, Astra Zeneca, Sinergium Biotech, etc.) and public health organizations (The CDC, WHO, EMA) are developing H5N1 vaccines13-16.

B. Treatment

Supportive care, with over-the-counter fever reducers and painkillers, enhanced fluid intake, rest and oxygen therapy, play a significant role towards relief from bird flu infections. Antivirals are the first medical interventions against infectious viral diseases. It is recommended that the treatment regime should begin within 48 hours of exposure or onset of symptoms. Due to these reasons, practitioners often prescribe them empirically until the lab results are back. Some of the common antivirals that are prescribed against bird flu are: oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza) or peramivir (Rapivab)13, 17.

C. Avian Flu Diagnostic Tools

- Molecular or Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs):

While many molecular tests [e.g., Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA); Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP); Nuclear Acid Sequence-Based Amplification (NASBA); Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)] can detect H5N1 in clinical samples, the preference of real time RT-PCR (with multiplexing capabilities) for H5N1 identification is due to the test’s high specificity and sensitivity teamed with quicker turnaround time for results. Given these advantages, the CDC endorses RT-PCR as the frontline diagnostic tool for the detection of H5N117,18.

- Serological tests:

Several tests, like Hemagglutination Inhibition and ELISA, which detect the presence of antibodies against H5N1 in poultry samples are available, but none have been approved for diagnostic testing in humans18,19. These tests generally have lower sensitivity and may display cross reactivity with antibodies against other seasonal Influenza strains. A microneutralization assay can be highly specific for the detection of H5N1, but it is a resource and time intensive technique that cannot be used in routine diagnostics. However, these tests are important tools in pandemic preparedness and vaccine evaluations.

Conclusion and Path Forward

The recent H5N1 Outbreaks viruses have taken a great toll on the poultry industry within the United States, which in turn has directly or indirectly impacted both healthcare and the economy at large. Pandemic Preparedness strategies that involve pharmaceutical as well as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), as follows:

- Surveillance: Monitoring the transmission rate and pattern is paramount for early detection, information to public health sectors and containment strategies. Surveillance enables identification and characterization of emerging strains and prompt risk assessment. Global (collaborative network of WHO11 and its Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System) as well as national Surveillance systems (e.g., Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service – APHIS), monitor emergence of AIV strains, allowing for timely intervention and response measures.

- Diagnostics: As viruses mutate and evolve, leading to novel and more pathogenic strains, diagnostic preparedness for AIV should encompass a comprehensive diagnostic approach to eventually include emerging and re-emerging strains (e.g., H7N9, H5N4, etc.) to ensure accurate and timely detections that will allow health officials and practitioners to make informed treatment interventions, ultimately protecting human and animal health.

- Effective Vaccines and Treatment: As discussed above, due to the constant evolution of viruses and potential for mutations to adapt to new hosts, research and development into more universal vaccines as well as novel therapeutics will be crucial to be effective against emerging strains with a pandemic potential.

Public-Private partnerships will be crucial to drive and accelerate the afore-mentioned strategies into action to combat the spread of disease and prepare for any potential pandemic. Enhancing global collaboration and promoting public health education will strengthen the preparedness and response strategies for future pandemics.

References

- de Jong MD, Hien TT. Avian influenza A (H5N1). Journal Clin Virol. 2006. 1;35(1):2-13.

- Peiris JM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 2007. 20(2):243-67.

- WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 evolution working group. Continued evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1): updated nomenclature. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2012. 6(1):1-5.

- Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V et al. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023. 1;55:102638.

- Hui DS. Review of clinical symptoms and spectrum in humans with influenza A/H5N1 infection. Respirology. 2008. 13:S10-3.

- CDC. What are the symptoms of H5N1 bird flu. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/video-series/symptoms-h5n1.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. First H5 Bird Flu Death Reported in United States. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/m0106-h5-birdflu-death.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- WHO. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024, 12 December 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who–2003-2024–20-december-2024. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Asian Lineage Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm. Accessed 4/14/2025.

- H7N9 avian flu strikes Mississippi broiler farm. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/h7n9-avian-flu-strikes-mississippi-broiler-farm. Accessed 4/12/2025.

- WHO. Global Influenza Programme. https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Avian Influenza A Viruses in People. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/index.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- American Society of Microbiology. Avian Influenza (H5N1) Vaccines: What’s the Status? https://asm.org/articles/2025/march/avian-influenza-h5n1-vaccines-what-status. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 AstraZeneca (previously Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 Medimmune). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/pandemic-influenza-vaccine-h5n1-astrazeneca. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Vaccines for pandemic influenza. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/public-health-threats/pandemic-influenza/vaccines-pandemic-influenza. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/hpai-interim-recommendations.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection and Testing for Patients with Suspected Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease or with the Potential to Cause Severe Disease in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/severe-potential/index.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

- CDC. CDC Report on Missouri H5N1 Serology Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/missouri-h5n1-serology-testing.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

References

- de Jong MD, Hien TT. Avian influenza A (H5N1). Journal Clin Virol. 2006. 1;35(1):2-13.

- Peiris JM, de Jong MD, Guan Y. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clinical Microbiol Rev. 2007. 20(2):243-67.

- WHO/OIE/FAO H5N1 evolution working group. Continued evolution of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1): updated nomenclature. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2012. 6(1):1-5.

- Charostad J, Rukerd MR, Mahmoud V et al. A comprehensive review of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1: an imminent threat at doorstep. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023. 1;55:102638.

- Hui DS. Review of clinical symptoms and spectrum in humans with influenza A/H5N1 infection. Respirology. 2008. 13:S10-3.

- CDC. What are the symptoms of H5N1 bird flu. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/video-series/symptoms-h5n1.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. First H5 Bird Flu Death Reported in United States. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2025/m0106-h5-birdflu-death.html. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- WHO. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024, 12 December 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cumulative-number-of-confirmed-human-cases-for-avian-influenza-a(h5n1)-reported-to-who–2003-2024–20-december-2024. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Asian Lineage Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm. Accessed 4/14/2025.

- H7N9 avian flu strikes Mississippi broiler farm. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/h7n9-avian-flu-strikes-mississippi-broiler-farm. Accessed 4/12/2025.

- WHO. Global Influenza Programme. https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines. Accessed 4/1/2025.

- CDC. Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Avian Influenza A Viruses in People. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/index.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- American Society of Microbiology. Avian Influenza (H5N1) Vaccines: What’s the Status? https://asm.org/articles/2025/march/avian-influenza-h5n1-vaccines-what-status. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 AstraZeneca (previously Pandemic influenza vaccine H5N1 Medimmune). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/pandemic-influenza-vaccine-h5n1-astrazeneca. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- EMA. Vaccines for pandemic influenza. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/public-health-threats/pandemic-influenza/vaccines-pandemic-influenza. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus: Interim Recommendations for Prevention, Monitoring, and Public Health Investigations. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/prevention/hpai-interim-recommendations.html. Accessed 4/2/2025.

- CDC. Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection and Testing for Patients with Suspected Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease or with the Potential to Cause Severe Disease in Humans. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/php/severe-potential/index.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.

- CDC. CDC Report on Missouri H5N1 Serology Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/spotlights/missouri-h5n1-serology-testing.html. Accessed 4/9/2025.